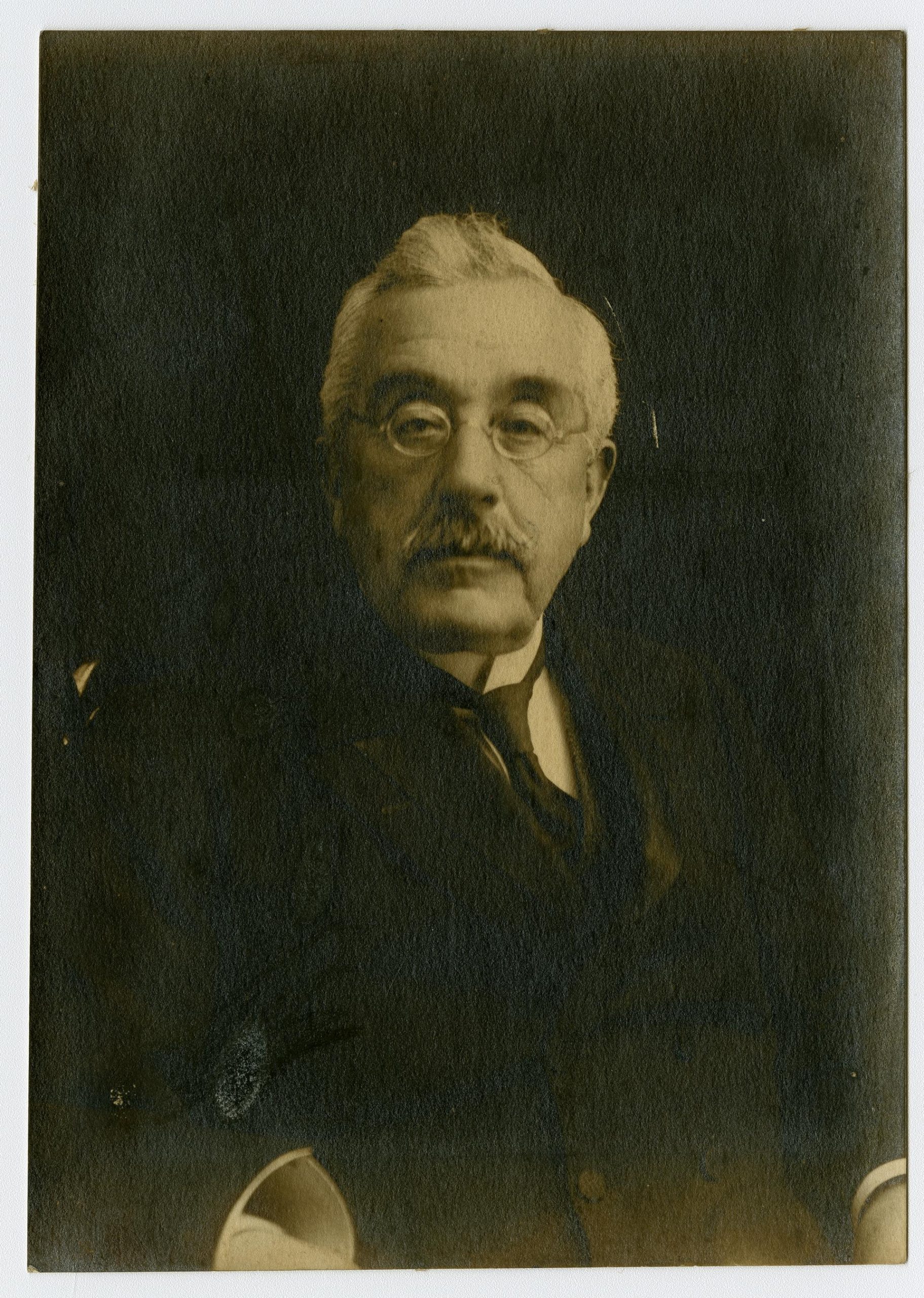

Joseph Cunningham

1st Superintendent of the Florence institute Trust 1889-1894

Joseph Cunningham was a Liverpool born flour dealer and baker. In 1889 he became the first superintendent of the Florence Institute for Boys after working at another boys institute in North Liverpool, The Gordon Working Lads Institute. Cunningham and his wife Elizabeth later went on to set up Cunningham Camps on the Isle of Man, the birthplace of the British holiday camp.

Joseph and his wife Elizabeth lived in rooms at The Florence Institute and during their five years here, Elizabeth gave birth to three children, two of whom later died at The Florence Institute. Elizabeth was also nursing her older sister Helen Winlack through the last stages of tuberculosis. Helen also died at the Florence Institute in 1893.

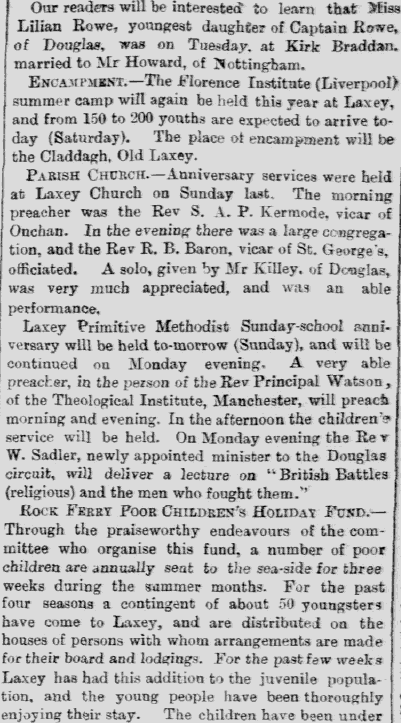

As Superintendent, Joseph was keen for Florrie boys to enjoy organised fitness and exercise in the fresh air of the countryside. In 1892 he arranged summer camps to Laxey on the Isle of Man for 150-200 Florrie boys and men; his wife Elizabeth had seens an advertisement painting the glories of Laxey as a holiday resort and had taken her own boys there for a holiday. In later years the annual Florrie camp was held at nearby Howstrake Douglas. Some further details about the camps can be found in the annual reports.

Joseph left his post as Superintendent of the Florence Institute in November 1894 following the last summer camp to the Isle of Man. By this time his working relationship with the committee members of the Institute had broken down when they felt the annual summer camps did not pay their way and the Institute had to make up the deficit.

The Cunninghams decided to organise any future camping holidays at Howstrake on their own account and they left The Florence Institute to set up Cunningham Camps.

However, before they were to leave The Florence Institute, Joseph Cunningham caught smallpox during an outbreak across Toxteth in 1894. The annual report records for that year show the Florence Institute had to close down for two months to be disinfected, cleaned and painted.

Both Joseph Cunningham and his wife Elizabeth went on to become pillars of Douglas society – he became scout leader on the island, a member of the House of Keys, and later was elected to the Legislative Council. Joseph Cunningham died in 1924.

Thanks to Jill Drower for permission to use extracts from her book, Good clean fun: the story of Britain’s first holiday camp, in this text.

Extracts from an interview with Jill Drower, great grand-daughter of Joseph Cunningham, from her book Good Clean Fun: a social history of Britain's first holiday camp.

Why choose to write about the Cunningham Camp?

I was always interested in the Cunningham Camp, because Joseph was my great-grandfather and in the eighties I felt that the record needed to be put straight. People kept referring to Billy Butlin as the father of holiday camps and yet there was plenty of documentary evidence to show, not only that Cunningham’s was operating on a large scale while Billy Butlin was still in short trousers, but also that the Cunningham Camp was an exact template for all the more famous camps that followed on afterwards.

Over recent decades, Cunningham’s has once again, disappeared from view. Books on holiday camp history still confine Cunningham’s to a pioneer, small-scale role with the Holidays with Pay Act of 1938 being given as the reason holiday camps initially grew in popularity. Although way overdue, The Holidays with Pay Act does not explain the sudden large increase in holiday camp numbers before the First World War.

It’s still the case that it is only really in the Isle of Man and in a few small academic circles that people are aware of the true origins of the British holiday camp.

The Cunninghams started out in Liverpool as bakers to Cunard and other shipping lines. What was it like being a baker in 19th Century Liverpool?

Baking as an occupation in the Victorian era was extremely hazardous, partly due to the coal dust and flour breathed in by those working in the industry and also due to the heat and extreme physical exertion required in the process. The average life expectancy was 42 years, but Joseph’s father, William Cunningham died in his thirties as did others working at the family bakehouses.

What do you think motivated Cunningham in those early years in Liverpool’s North End?

The area where the family settled – by the docks in the North End – was notorious for its destitution, beer houses and brothels. Many migrants escaping the Irish famine settled in this area, unable to afford the onward journey to America, so Joseph would have witnessed first hand people living in appalling circumstances and in a state of drunkenness or near to starvation. The Presbyterians in Liverpool at that time were active through a number of different meeting halls and congregations and Cunningham’s own particular congregation believed in taking the Gospel out to the people and providing real practical help. This was how he built a following which led him to the Gospel Hall, the Gordon Institute and then later, the Florence Institute.

It has been said that Joseph Cunningham was sacked from his job at the Florence Institute. Could you say something about that?

Yes, he was given three months’ notice to quit in the Autumn of 1894. Extracts from the Florence Minutes in the appendix of my book, show the steady decline in the relationship. I think the problem was that Joseph Cunningham was, as an independent tradesman, used to running things his own way. He knew what wealth there was in these philanthropic institutes and could not understand why the Committee withheld money for more costly prizes and more outings to the country. The whole point of these charitable institutions, after all, was to improve the quality of life of their members. The Committee for their part did not trust the fact that he was a tradesman, and felt he was lax with both money and discipline.

How did Laxey and the Isle of Man become a holiday destination for the Florence boys?

This was suggested by Elizabeth Cunningham. When she was a young married woman Elizabeth noticed a newspaper advertisement painting the glories of Laxey, as a holiday resort. She took her two boys there that summer, and was found lodgings. The Florence boys were later taken there by Joseph on her recommendation.

How important was Elizabeth’s role to the success of Cunningham’s Young Men’s Holiday Camp?

Until now, Elizabeth’s role has been seen as supportive in relation to the Camp rather than instrumental to its success. She has been praised more for her many charitable commitments than for the efficient running of the world’s largest ‘hotel kitchen’. In fact, Joseph could not have built up the Holiday Camp without her know-how. Joseph was the one with the grand ideas and he was the ‘horse whisperer’ – the one with the ability to turn around even the rowdiest lads – but he needed Elizabeth’s organisational skills to make the Camp a going concern. Her management was excellent, given her accountancy training, and her great head for figures. She herself said that she was never physically out of the Camp between May and September, so I believe her role to have been central. I also believe that great innovations, such as Ellerslie as a model farm, came from Elizabeth. She was very widely read and I think this idea came from her, although I cannot prove it.

Much has been said about Cunningham’s being a men-only and teetotal holiday camp. Do you talk about this in the book?

Yes. What I found interesting about the rules was not that they were strict. They weren’t by Edwardian standards. If you think about the early 1900s, boys and girls went into school through separate entrances and there were many places, such as swimming pools or saloon bars where men and women were segregated. But what is surprising is that the men-only teetotal rule continued unchallenged for so many decades. My uncle Joe (grandson of the founders) did shifts at the entrance in the 1930s and said that after closing time, if a camper was able to walk through the gates supported by his friends, then he did not get stopped. In other words, by the late 1930s the teetotal rule was unworkable.

The other interesting thing about the men only rule is that it has led some to believe that women were never allowed to enter the Camp. This was not true. Women were not allowed into the camping grounds where the tents were pitched, but were free to roam the gardens, the palm court and roof terrace and were encouraged to come and join the morning dances. In fact, it became something of a local joke that women made a beeline for Douglas as the number one singleton tourist destination.

THE FLORENCE INSTITUTE

- 0151 728 2323

- info@theflorrie.org

- 377 Mill Street, L8 4RF

- We are open: 9am – 6pm Monday to Friday.

Registered Office: The Florence Institute Trust Ltd, 377 Mill Street, Liverpool L8 4RF. Charity Registration No: 1109301. Company Registration No: 05330850 (registered in England and Wales).